by Logan Ward

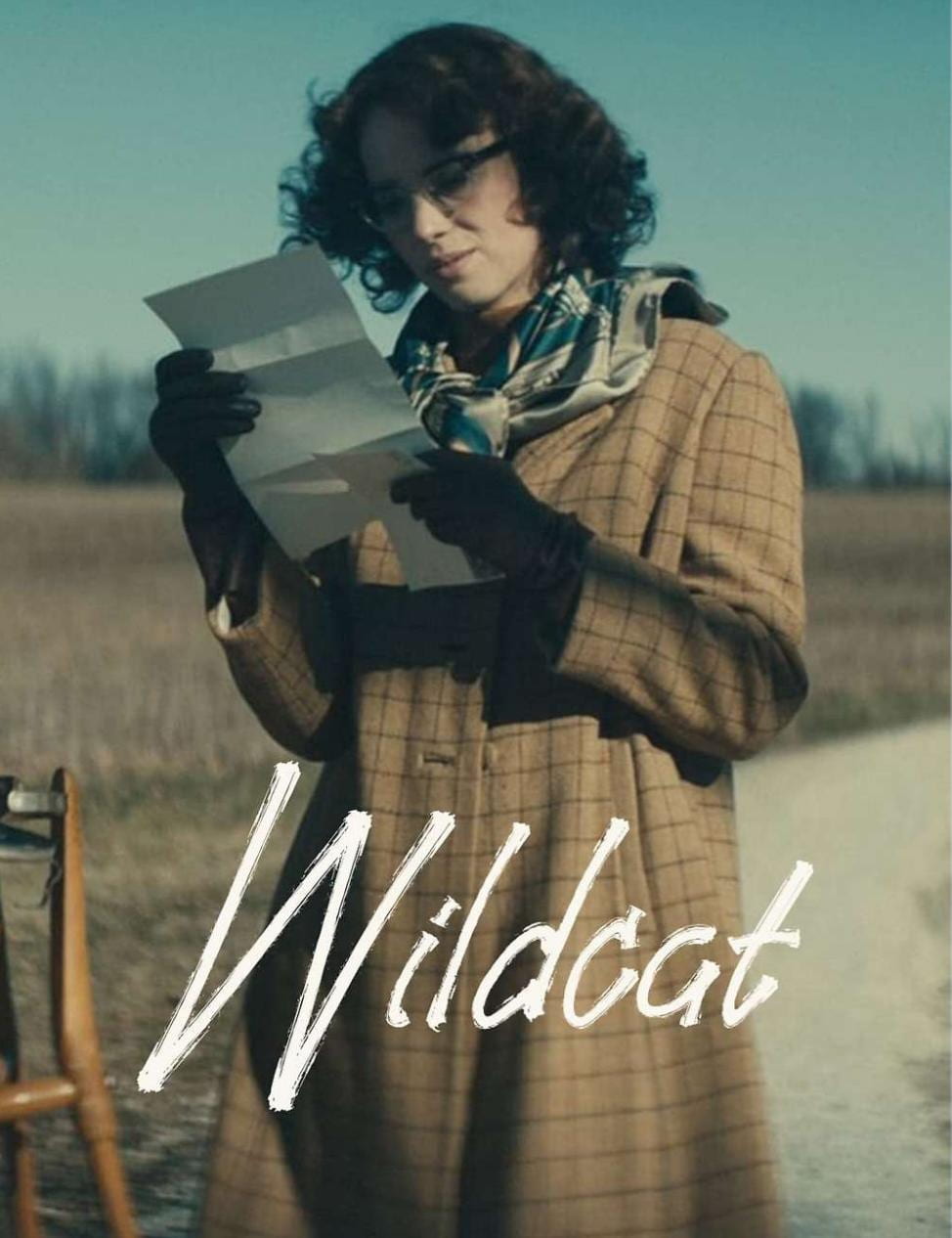

On Saturday, April 13, a group of Centre students (myself included) – who took the legendary Dr. Mark Lucas’ Flannery O’Connor course over CentreTerm – were treated to a dream opportunity: an advanced screening of the Flannery O’Connor biopic Wildcat at the Kentucky Theater in Lexington, followed by a Q&A session with director Ethan Hawke and actor Steve Zahn. Accurately described by Ethan Hawke as a “fever dream,” Wildcat is not a film for the uninitiated, and is very clearly targeted towards fans of the Southern author’s work. Wildcat is a film that I think is worth talking about, so whether you’re a devoted acolyte of Flannery or someone who I’m risking sounding like gibberish to, I’ll dive in — and do my best to share my thoughts on Wildcat with you.

My first introduction to Flannery’s work came with Dr. Lucas’ class. For the entire month of January, my primary academic obligation at Centre College was reading and analyzing her work. For someone who hadn’t read much of her work before, I experienced some pretty serious system shock — but in a good way!

Born in Savannah, Georgia, Flannery spent most of her life living with her mother at their Milledgeville, Georgia farm after brief stints in New York and Iowa City trying to gain approval in the elite writing circles of her time. Spending almost the entirety of her adult life in Milledgeville was, however, not her first choice — she was confined there upon developing lupus, the same disease which took her father’s life.

Flannery’s existence by no means went according to the expectations of her surroundings and time. She was a devoutly Catholic writer in what she called “the Protestant South.” She sought to challenge the institution of segregation in her writings through savagely lampooning the racist and bigoted attitudes of those whom she was cooped up with for the rest of her life — close family members included. However, this only strengthened the impact of her writing in that these characters were in no way stock, cartoon racists and bigots: they were as human as any other characters in her work. However, this is all to be expected in a Flannery O’Connor story. Flannery never shied away from portraying human nature in full – the ugly and morally grotesque elements included. That being said, the moral lessons of her stories don’t end at “Look how bad everything and everyone are!” Her stories frequently end with the administration of grace upon her characters, generally non-believers and/or Christians-in-name-only, guilty of a wide variety of sins, the aforementioned bigotry included.

Wildcat is a brief portrait in Flannery’s life following her return home to Milledgeville. While she initially plans on returning to New York City, she soon becomes ill. She later learns from a relative that she’s contracted lupus, the same disease that killed her father, and that her mother, Regina, has been hiding it from her. As it becomes clear she’ll remain in Milledgeville indefinitely, she keeps on doing the one thing she can: writing.

Interspersed throughout the film are adaptations of some of Flannery’s work, the short stories “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” “Revelation,” “Parker’s Back,” “Everything that Rises Must Converge,” and “Good Country People.” All of the stories cover events ranging from the poignantly mundane to the downright absurd.

As I mentioned earlier, Flannery’s stories all come with a “grace moment” which Wildcat doesn’t adapt in some of its takes on her stories. That’s not to say the theme of grace is absent from the movie, however. One of its best scenes is an extended conversation between Flannery and her priest — who, for some reason that I’m not complaining about, is portrayed by Liam Neeson –where Flannery desperately begs for her own grace from God. However, one of the strongest adaptations in the entire movie, “Revelation,” is missing its ending — its grace moment, and also one of the short story’s most iconic scenes. “Revelation” follows Ms. Turpin, a deeply bigoted racist and classist, who gets some sense knocked into her after a young woman throws a book at her in a doctor’s office, fed up by her racist ramblings. The story famously ends with Ms. Turpin receiving a vision demonstrating the classic Christian principle of “the last shall be first, and the first last” as she watches black folk and “white trash” ascend to Heaven before her. The film adaptation ends at the doctor’s office, though still portrays an earlier vision scene in the story where a depiction of Jesus Christ asks Ms. Turpin if she’d rather be reborn as black or white trash. Though most of what makes Revelation the story it is is still there, the absence of its ending detracts from the power of the original story.

Another issue with the movie is that I feel those who aren’t super familiar with the author’s work will feel blindsided by what they’re seeing. “Revelation,” again, is another good example of this. During the Q&A, Hawke and Maya expressed their worry about how modern audiences might react to the story’s blunt and bizarre portrayal of racism. It’s a provocative scene, to say the least. However, Jesus’ deadpan, clearly-mocking tone coupled with Ms. Turpin’s shell-shocked reaction I can’t see leaving my mind any time soon.

All I can say is that I find catharsis in a movie that lets you laugh at people like Ms. Turpin – people who take themselves and their ignorant pretensions about the world far too seriously. In an era-defined by self-righteous rants on social media and on every twenty-four hour cable news network, it’s a catharsis we all need. But, Ms. Turpin is still a person too. The movie doesn’t for a second entertain her nonsense, but it acknowledges that like all of us, she has a capacity to learn her lesson the hard way.

There’s a lot I could say about Wildcat, but at this point, I’d compel you to watch the film yourself. All in all, Wildcat was a wonderful filmgoing experience that was just as thought-provoking, intense, and absurd as the stories that inspired it.