by Daniel Covington

Background

In the past semester, many Centre College students started to wonder if campus wide emails were being written by AI. Whether or not those emails are truly written by AI is beyond the scope of this article, but the fact is that people are questioning what the place of AI in schools is in the rapidly changing AI architecture flooding our everyday existence.

Even since 2024, Microsoft has started including its own large language model Copilot on all Windows computers, visible in the taskbar at all times. Those who have used it and other AI models to the greatest extent have put their education in jeopardy. All the while, over the past 3 years, AI has grown, and so have its use cases. This has changed how professors all over the world teach their classes. But there is no clear way forward. As the professor I interviewed says, “It’s the wild wild west”. No one including Centre has a real answer because this technology is unprecedented. People are learning by trial and error without often really understanding how these tools work. Even so, we absolutely need a clear AI policy at Centre College.

I will be interviewing Professor Thomas Allen. Just like AI, he is a bit of a jack of all trades, but most importantly he is a professor who has studied AI since its inception and has asked himself, should AI be in higher education and if so how do we ensure a positive impact on students? It should also be mentioned that Professor Allen is also teaching the CentreTerm class, AI in Everyday Language, where we discuss this very topic. Originally, I wanted to interview a few professors, but because of time and Professor Allen’s very middle ground approach I have decided to interview him to get a case for both sides and an understanding of how this new technology works. In interviewing an expert we will be discussing AI in higher education, both the good and the bad of this direction.

What is the use case for professors?

In talking with professor Allen, I wanted to see how he found it useful for professors. He states that “One of the best use cases is developing a tool, a game, or a demo that makes a conceptually difficult topic easier to understand.” He goes on to explain, “I could code these myself, but it might take several days—and during CentreTerm, there is zero chance I’d have that kind of time. With AI, I can create a visual that better illustrates an idea in 45 minutes. It allows us to enhance our teaching with better examples and graphs that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.”

Can AI be used to help students study?

When talking about responsible use I wanted an example of a healthy way of using AI and a way of using AI to cut corners that would result in hurting your education. Allen first focused on how AI can be used as a tutor. He states that “”There are positive ways to use this that help learning and negative ways that hurt it. A positive way is using a large language model to explain a concept that didn’t make sense during a lecture. You can ask it, ‘Could you explain how the chain rule works?’ and if it still doesn’t click, you can ask follow-up questions like, ‘What does f-prime of x actually mean?’ It offers a level of interactivity that a YouTube tutorial can’t. You’re approaching it as a way to understand better and improve yourself.”

How do students use AI to hurt themselves?

Now Allen focuses on how AI uses to cut corners, and how this hurts students. He also gives an analogy to really understand why we sometimes do busy work or long seemingly pointless readings. At the end of the day almost nothing we do in education is pointless. Everything is given for a reason, that reason just isn’t always understood by students. He says, “I had a student who played soccer ask why we couldn’t use chatbots to write code. I asked him, ‘Has your coach ever told you to run 10 laps? Suppose you told your coach you were going to use a scooter to get around the field instead.’ The coach would say no, because those laps are there to make you physically conditioned to play the sport. Riding the scooter might be pleasant, but you aren’t doing anything that helps you. If a student just types in a prompt and pastes the answer, they are short-circuiting their own learning.”

What other ways can it help students?

Professor Allen made a great point for students with disabilities. AI can really help level the playing field: “I think these technologies can greatly enhance the lives of people with disabilities. When I was in graduate school, I had a hand injury that made typing very painful. I had to use my voice to write code, which was incredibly tedious back then. Today, being able to speak to a model and have it produce code would be a wonderful gift.”

What are the issues with AI on the professor side?

The pressure to use AI isn’t just on students. When talking to Professor Allen I realized that professors, particularly in bigger state schools, feel that very same pressure. Professor Allen shares a story where a dean at another institution is trying to have professors use AI to grade papers faster instead of giving professors adequate time and/or help. He notes, “Pasting student assignments into ChatGPT potentially violates FERPA [federal privacy laws]. Beyond that, our research shows that chatbots are not good at evaluating student essays. They lack the context of the class—they don’t know what was taught, what the level of the course is, or what the students have read. Without that context, AI can’t give a reliable answer. Using it as a shortcut doesn’t just produce poor feedback; it causes genuine harm to the educational process.”

This leads Professor Allen to worry that education will just become transactional. Instead of Centre college, we could become the Centre College Factory: “We specialize in 2 products, papers and resumes.” Furthermore Professor Allen says that “If the whole purpose of college is just to generate a paper or math answers to list on a resume, then we are approaching it the wrong way. College is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to develop relationships with faculty and peers. If we become like machines that just pass tasks off to other machines, we miss something fundamental about being human. Part of what makes Centre College unique is the chance to inspire and be inspired. If our only goal is to ‘achieve more’ and ‘generate more,’ we are just feeding into a cycle of grasping for more text in a world that is already drowning in it.”

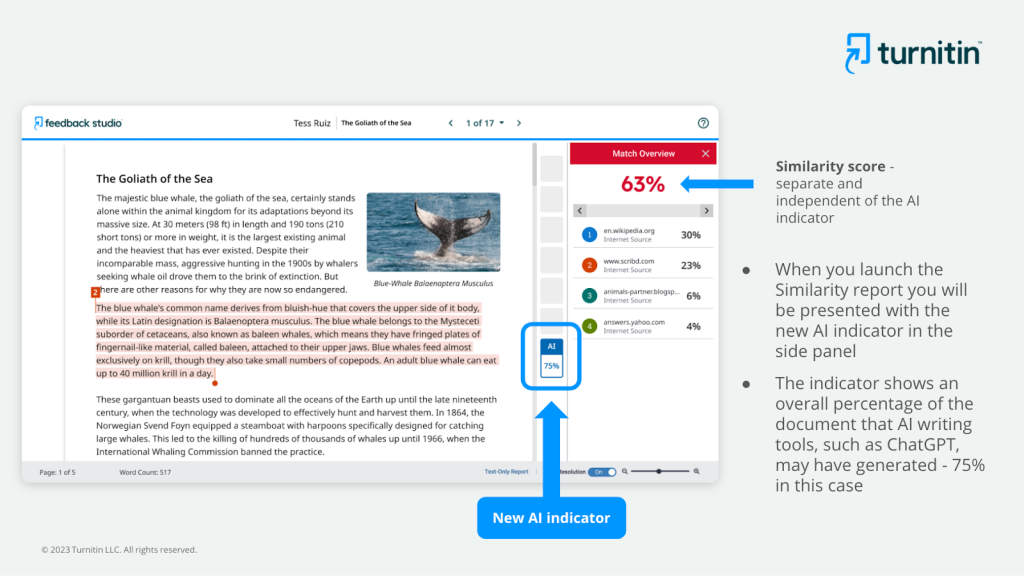

Does Turnitin do more hard than good?

Since Professor Allen studies AI he has done a deep dive to see how we can fight academic dishonesty. Ultimately this led him to start researching turnitin.com, a software that looks over student papers for plagiarism and use of AI. Compared to seemingly all other professors on campus, he doesn’t use it. He believes that it often “solves” a problem with AI by creating another. “The first thing I do when I create an assignment on Moodle is turn off Turnitin,” Allen reveals. “As soon as you turn that service on, it sends your work to a private server. Turnitin then takes the work you created for your class and, according to their own policy, allows it to be used to train AI models. It’s a business model where they solve the problem of cheating by taking student information—usually without the student having any choice in the matter—and putting it into a database to sell to third parties.”

For Professor Allen, this does nothing to help the students and he says, “I don’t like the idea of catching people cheating by taking their information to build the very machines we’re worried about. It’s a system that treats student work as raw data for a product rather than a personal educational milestone.”

This is not even to mention the fact that this is a form of AI, and the number that Turnitin spits out isn’t how much AI is being used, but the likelihood. This often results in false positives sweeping up both students who did cheat but also many who did not.

How to prevent cheating?

I asked Allen what professors should be doing to ensure that students cannot cheat easily. When taking an exam for his class (one of the first few he has done on a computer in a long time), he seemingly had several tricks up his sleeve. After all, he is a tech guy.

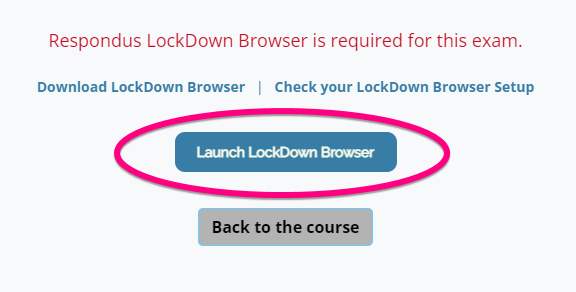

At the base, he simply watches students take the exam, but from there it gets a little more complex. If he sees something but isn’t sure, he can check web traffic (since we are also in a computer lab, he has a bit more control over the computers). Each computer has software installed which randomly takes pictures of your screen during the exam. He also has the option to use the LockDown browser software. Notably, Professor Allen doesn’t want to do any more than this. He says that “Any method of detection that is nearly 100% accurate in catching cheaters will necessarily sweep up a large number of innocent people. During my GRE, I was watched by cameras the entire time. When I got nervous and put my hands in my pockets, they immediately came in to check me. That level of suspicion creates immense stress. If students feel like they are being treated as rule-breakers before they’ve done anything wrong, it creates a nerve-wracking environment that can lead to worse performance. We have to find a way to encourage integrity without turning the classroom into a high-security prison.”

What should AI policy look like?

Professor Allen calls the state we are in the “wild wild west for professors.” There is no school-wide policy. Everyone is doing what they think without any real guidance; this is the same for professors and ultimately for students. Because of this, he says there needs to be some type of default policy that can help guide everyone. “It is difficult, in principle, to design a policy that works for every class at a place like Centre. What we need is a ‘default’ policy,” Allen suggests. “This would state that if a syllabus doesn’t mention AI, the baseline is that students may use it to support their learning, but not to complete assignments. This puts everyone on the same page while allowing instructors to override the policy based on their specific goals.”

While a default policy is great, Professor Allen acknowledges that almost all classes and especially majors work completely differently. After the default policy there needs to be a policy for every class. “We teach everything from music and art to physics and history. There are times when using AI is beneficial and times when it is detrimental to the learning process. A good policy should also address the ‘controversial’ side: when is it appropriate for staff or faculty to use it? We need to be upfront about our own use cases so we can lead by example.”

What are the issues that hit home?

As AI grows not only will we be working with the issues of using it in education, but many of the problems will start to hit close to home. “These models use a tremendous amount of electricity. That power has to come from somewhere—typically coal or renewables, both of which have a cost,” Allen says. “Even if we put solar panels everywhere, that farmland is no longer available for production. Eventually, the harm to the environment may exceed the benefits we gain. It needs to be part of a larger conversation about the cost and the benefit, much like how we discuss the carbon footprint of flying to conferences or driving personal cars.”

Besides the environmental issues there are also the training data issues. With AI being trained with everything on the internet “It’s not possible for the people who train these models to know everything that’s in the data,” Allen warns. “If you sweep up writings from the 1800s, you are including ideas and prejudicial language that are deeply harmful today. The model begins to mimic and encode those biases in its future output.”

Lastly, that leads us to the issues of copyright. Imagine that you are trying to get so much data that it is quicker to steal it online than pay for what you are using. “Researchers swept up massive amounts of copyrighted material because it was publicly available on the internet, but that circumvents the way creators are actually compensated for their work. Whether that is illegal or not is for the courts to decide. It just shows how technology has gotten ahead of the law and society. At the Centre, that means I have to constantly rethink my teaching. How do I design a test when students might eventually have AI built into their glasses? I don’t really know the answer to that yet.”