by Olivia Barker, Arts & Leisure Editor and Staff Writer

Currently, there are 575 students working on Centre’s campus. By the end of the year, this number will be near 700. With such a large margin of Centre’s students employed on campus, work-study has an incredible impact on Centre’s culture, seen by many students as the ideal avenue for making a buck without sacrificing their foremost role as a student.

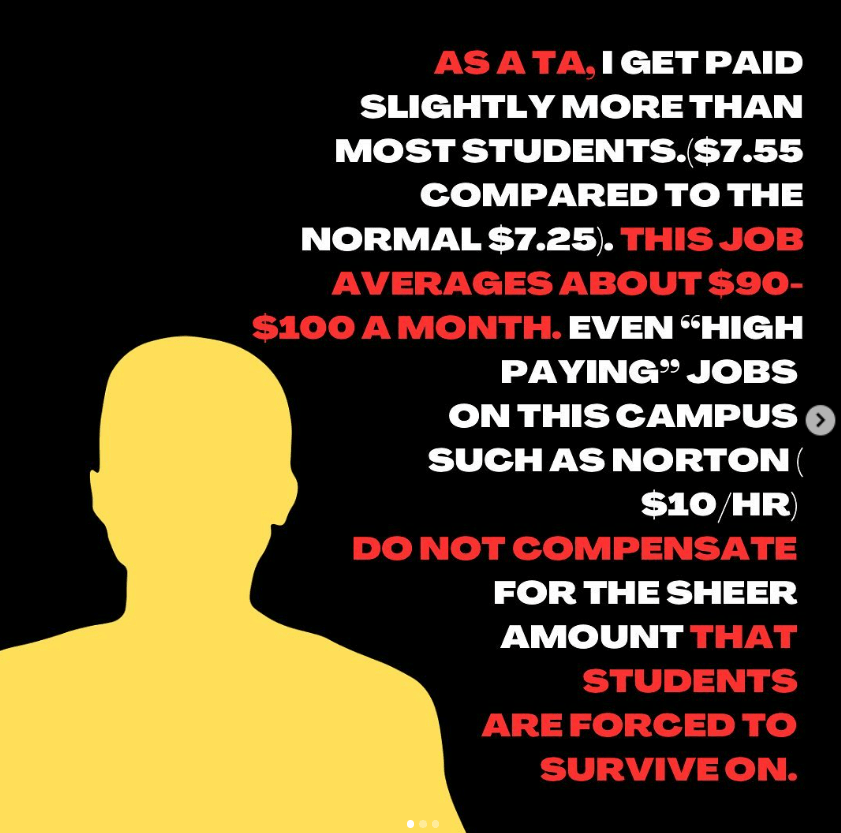

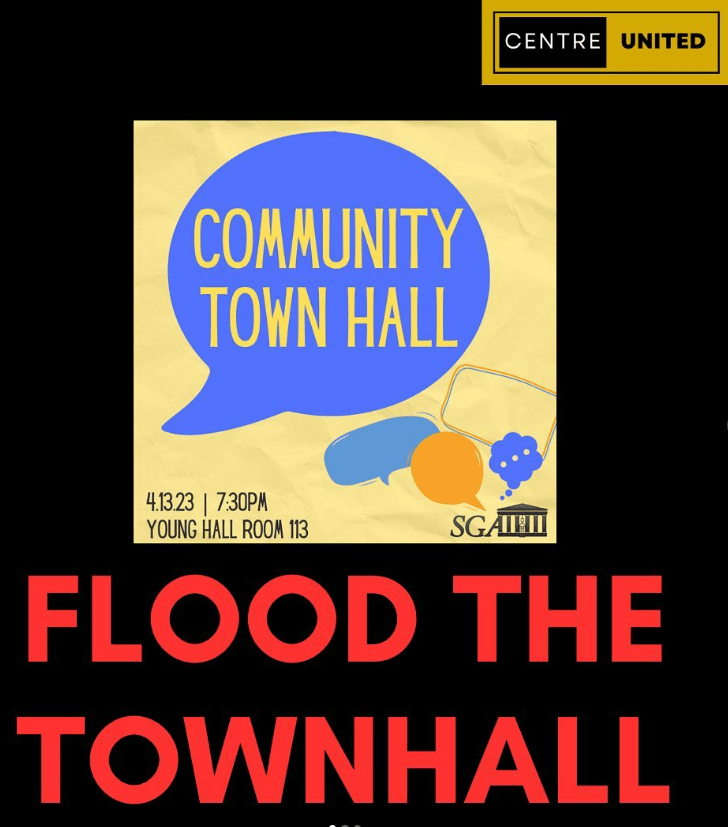

Last year, however, the idealism of these positions were challenged in a campaign known as “Centre United.” Centre United was formed amongst a group of students who raised concerns about student workers’ compensation among other issues of safety and transparency on Centre’s campus. Although their Instagram account was active for only a short period (from April 4th to April 12th), they gained a considerable following of 466, regularly posting the anonymous commentary of Centre students on issues they had raised. The account specified the groups qualms with student compensation, stating that “as national inflation increases, student workers have not been given a raise or sufficient support.” But are these concerns valid, or merely the ramblings of dissatisfied minimum wage employees?

The answer, it seems, depends greatly on the category under which student workers fall: while many students work campus jobs casually, others are working under their qualification for federal work-study, a program designed for college students to work in order to make payments towards their education, allowing a greater sum of working hours. In this instance, it seems reasonable to challenge the school’s majority minimum wage positions; logistically, with Centre’s average cost after aid at about $20,000 a year, students would have to work roughly 77 hours a week throughout the school year in order to pay off their remaining sum. Of course, no student expects to pay 100% of their remaining costs through their on-campus position, but it is notable that to make enough to pay even a fourth of this expense at a minimum wage job, students would still need to work almost 20 hours a week during the school year on top of classes and schoolwork.

And compared to other Kentucky universities, Centre seems to be far behind in student wages. In the 2022-2023 school year, Murray State had average student wages of $8.15 an hour, Morehead University of $9.01 an hour, Western Kentucky University of $9.14 an hour, University of Louisville $10 an hour, and Northern Kentucky University of $10.65 an hour. Meanwhile, the majority of Centre’s student positions—with the exception of advisory positions and those requiring special skill sets—pay an hourly wage of $7.25 (the federal minimum wage).

In a Centre “town hall” meeting last year, for which attendance was advertised on Centre United’s instagram page, one student challenged this division, questioning the panel of Centre faculty as to why Centre couldn’t have starting student salaries more in line with other universities, referencing the University of Kentucky’s roughly $10 starting student wages. A school representative responded by comparing the environment of a school in Lexington versus Danville: she articulated that UK was “competing against Lexington employers”—a competition that, no doubt, is not nearly as prevalent in small-town Danville, where students have much fewer options for off-campus work. Moreover, she added that the cooperation students receive from their on-campus employers makes Centre’s student work environment unique in a positive light—the flexibility allows for students to truly prioritize their academia.

While she did mention that higher wages were worth looking into, the response of the panel to another question regarding tuition increases raises questions over whether the funding for such a change is even available. The panel articulated that Centre is a tuition-dependent, nonprofit school that had for the first time reached a budgetary deficit, forcing proponents of higher student wages to question whether the college can even afford to make the change.

One student worker in one of the higher-paying positions at Centre, at $12 an hour, offered his perspective on his role as a student worker. “I think that the college (and the wider academic community) view on-campus jobs as ways to earn extra money, not to make serious attempts to pay off student loans or costs associated with being a college student.” This is certainly true for many student workers — often, they are looking to get accustomed to working and to make some extra cash for recreation or, in this student’s case, expenses such as gas, insurance, and groceries.

Another student, working a minimum wage position at Centre, adds that she also uses her wages for non-school related expenses—food, recreation, and sometimes groceries—and doesn’t expect it to completely cover student expenses. She adds, however, that “for me, it’s an okay amount, but also I think that if you were using this amount of money to cover all student expenses, or a significant part of that, or for loans and tuitions I’d say it’s not.”

Moreover, this student offered the solution that Centre diversify their job options for those students looking to make payments towards their education—she explained that by creating jobs that were “more involved” and “higher paying,” students would have more of an opportunity to make more money in exchange for taking on a more active position.

While it may be unreasonable to expect Centre administration to increase wages for all of its hundreds of workers at once, small steps like this one certainly seem feasible. And for many students, it may come back to another of Centre United’s core platforms: transparency. Although students seeking higher wages may understand that the college cannot afford immense changes at this time, it might at least ease their minds to have an idea of what their over $50,000 worth of tuition is being put towards instead.

Centre United representative Ben Justice comments on how they are striving for this greater financial transparency alongside their primary goal of wage increases, expressing how they are working on surveying the study body about their needs as they lobby for administration to be more open about their efforts to increase student wages. The group–now referred to as the Student Worker Organization, or SWO–is also looking to promote greater recognition for students working to further the diversity and inclusion efforts that Centre is so adamant about.

Unfortunately, the group has struggled to form into a viable legion as most students are unaware of the SWO, preventing them from gathering enough participants for the option of formally unionizing. “However,” Justice remarks, “having a union with the workers so we have representation and an organized voice in the college will be a net positive for everyone.”

He encourages students with investment in their cause to step forward and help organize efforts that will allow the newly organized group to gain support, insight, and credibility; Kevli Sheth, alongside Justice, reminds Centre students that they are always open to questions about their cause.

Despite challenges, Justice remains enthusiastically invested towards the work of the SWO: “Our student workers in the group have different reasons for taking action. Some students are paid minimum wage or near-minimum wage for intensive jobs. Even if the jobs are not intensive, they are nonetheless essential to campus operations.”

It is, after all, the work of students that on many levels allows Centre to operate on the level that attracts the eyes of so many prospective students, alumni, and the community; it seems necessary to have someone advocating on their behalf.