BY JAKE MCGUIRK – STAFF WRITER

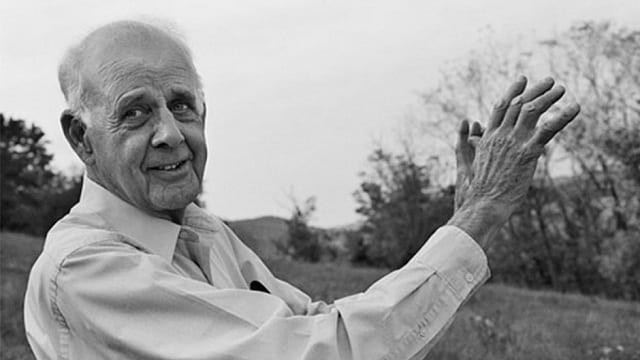

Wendell Berry visited Centre this past week to read from his work and converse with students. He came to us, radiant and witty, to share his intellect and poetic spirit. If you read Berry, you know his genius. If you heard him speak, you know his heart. I will attempt to offer here a glimpse into Wendell Berry’s philosophy in case you missed his visit, or if you just want more.

Wendell Berry is a Kentuckian and a poet. Berry seamlessly marries language and spirit to proffer his wisdom on life. From political critiques and environmentalism, to love, faith, and happiness, Berry writes from the heart and the mind. He is clear and direct and beautiful at once. Reading Wendell Berry is revelatory, refreshing, and challenging in the most beneficial sense of the word. He writes and speaks in advocacy of love, of peaceful and simple living, of care for the earth, and, to those same aims, of the many mistakes we have made as a society that bar our way to the good life. Generosity and modesty are invaluable virtues to Berry which stand in valiant opposition to so much of what our world has become.

He writes of places – mostly places in Kentucky – and has the singular ability to make you feel as if you are there. His words are in the places he describes, not superimposed on them. In his poem, “How To Be a Poet,” Berry writes that there are “no unsacred places; / there are only sacred places / and desecrated places.” The land is indeed sacred to Berry, and he thinks it should be important to us all. He decries the way we exploit and abuse it, be it industrial mining or misguided conservation efforts. Moreover, we forget that nature is not only the land, but also the creatures that live on it, including people. “You mustn’t ever separate the land and the people,” he warns.

Berry is concerned with Kentucky specifically. Like many, he sees a state in decline. Berry attributes this to the coal industry and the decreasing number of small farms. It is made worse by politicization, usually at the further expense of Kentuckians. For example, on the supposed “war on coal,” Berry says, “it is an exploitive and irresponsible phrase that condenses a complex matter into a quotable falsehood. The people hollering about the ‘war on coal’ are the same bunch who allow these regions to become a single product economy, and to then be ruined by that single product economy.” Coal mines first provided work for Kentuckians, but also made them dependent on it. Then, machines replaced the workers, and left them with nothing. Elsewhere in the state, mechanized agriculture replaced farmers and made it impossible to earn a modest living without possessing immodest amounts of money to invest in machinery.

Berry thinks there is plenty of potential for Kentucky despite the destruction wrought by industrialization. Berry laments that “this state is half-forested and nobody talks about it! And nobody talks about the people, other than saying they need jobs.” He prescribes agriculture and forestry for Eastern Kentucky. There is not much arable land, but there are trees, and there is room to raise enough crops to subsist. “We oughta be feeding the people,” Berry says, rather than being concerned with what products they can make to export. They need not grow food to sell in bulk. Most politicians and businesspeople would probably argue that there is no sense in producing something or investing in something that cannot be sold. Berry thinks that is nonsensical, that people should grow for themselves and their local communities.

Berry’s ideal economy is one that deals little with money, and more with life’s essentials. Why focus on symbols of value like currency, which is valueless, when we should care more about those things which really are valuable? Food, neighborliness, and love should be our currency. One of his favorite sayings describes how people in agricultural communities of his childhood thought of their work: “Nobody’s done until everybody’s done.” If one farmer hadn’t finished harvesting, the rest of the community helped out. Until he or she finished, no one was finished. Berry stresses that there was no talk of money or transaction in this situation. “You could stay for dinner if they offered it, but you couldn’t take any money,” he recalls. This way of life, Berry says, is “subversive” to the sorts of economic principles we are taught. It is incompatible with what Berry calls “the ‘holy rite’ that capitalism confers on the big to destroy the little.” It is important, then, to not compete, but to practice neighborliness. “If you have a neighbor,” Berry says, “you have help.”

Berry stresses the importance of land to the economy. While he has lofty environmentalist sentiments, his concern is very much a practical one as well. It may seem a less important problem than something like poverty or unemployment, but Berry points out that, “The problems of the city start in the country.” He discusses how the mechanization and industrialization of agriculture destroyed small farms and forced people to sell their land and move to into cities. He says, “City life is not inherently wrong – it’s where things concentrate, like schools, the arts, conversations…but cities have too many people in them who don’t have anything to do.” And jobs, he says, are not what matters, but rather work. That is to say, work that people can “be dignified by” and proud of, like growing and making things.

—

The only higher privilege than reading Berry is speaking with him directly. He is genial, hilarious, and thoughtful. His humor, somewhat dark, but always lighthearted, is accompanied by a beaming smile. Though he laughs, he is very serious. He is concerned about our world, that it has become mechanistic, greedy, and destructive.

Berry has a beautiful vision. He seems very young in that respect, possessing a sort of idealism usually associated with millennials. I asked Berry what he thought of idealism, which is often viewed today as impractical and a mark of ignorance. He said, “If you take idealism to mean having expectations higher than what can be attained, then I’m not an idealist, because I don’t expect much! Ideals, though, are indispensable for guiding us to what is right.” He cautions against idealism without the willingness to act in pursuit of ideals. Our generation should take heed of this advice. While our vision of the world may seem unattainable, it important that we always work for it and not settle for less.

Berry certainly practices what he preaches. He farms and cares for his little patch of land and the people around him. He seeks ways to live better and counsels others on how to do the same. He is a farmer who lives the good life, and who thankfully has an amazing gift of language that enables him to share his life with the world. He is a neighbor to everyone.

I want to end with some of Berry’s words. I find the following poem relevant now more than ever:

“Even in Darkness”

Even in darkness, love

shows the circumference

of the world, lightning

quivering on horizons

in the summer night.

Wendell Berry, 1994