BY JOHN WYATT — SPORTS SECTION EDITOR

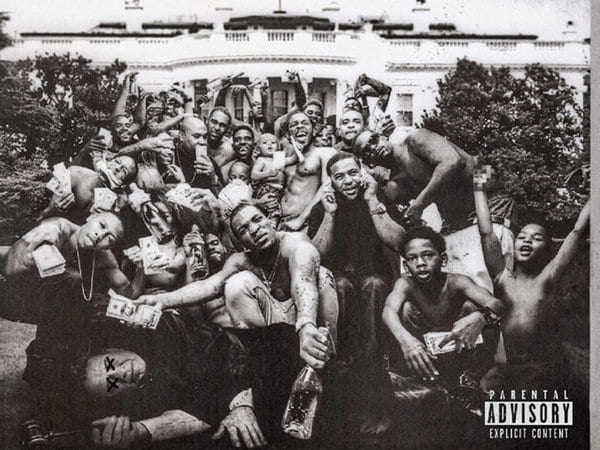

Throughout the history of music, there are moments where artists tap into some force or state of mind that produces something truly special; something that fundamentally alters and shifts the culture and latches onto people on multiple levels. Kendrick Lamar’s third album (second major label release) To Pimp A Butterfly is one such moment.

Fans, critics, and artists gave nothing but praise to the Compton, CA, native since the early days of his career. His first album Section .80, showcased the rapper’s versatility, as well as his willingness to tackle dense social issues head on with a thoughtful and nuanced approach. It wasn’t until his major label debut, good kid, m.A.A.d city, though, that he launched himself into rap stardom. Good kid was instantly declared a classic by fans and critics. For critics and hip-hop heads, Lamar was something of a savior for his ability to stay true to the “essence” of rap and speak on the social and political issues he felt the need to address hidden under radio hits and party anthems. Besides a few guest contributions and a legendary verse on Big Sean’s control, Lamar went silent, slowly toiling away on his latest masterpiece.

Lamar’s newest album adds to his repertoire, combining strong social commentary, a critique of the music industry, and 60s and 70s musical influences.

If you expect this album to be another “Bitch Don’t Kill My Vibe” or “Swimming Pools,” you’re going to come out disappointed. Lamar takes the roots of modern hip-hop, but drowns them in jazz, Parliament-era funk, soul, and even classic G-funk West Coast rap with tons of live instrumentation mixed in for good measure. The opening track, “Wesley’s Theory,” smacks you in the face with the funk and some monster basslines by the bass wizard that is Thundercat and Flying Lotus-produced beats. Here, Lamar raps on the pimping of black entertainers by the music industry, switching perspectives between a naïve young rapper and the music industry, and by extension government institutions (referred to as Uncle Sam throughout the album), circling the young rapper like a vulture waiting for its next meal.

The funk and swagger reach an apex though on the long anticipated “King Kunta.” The track sounds like its pulled straight out of the 70’s funk era dominated by bands such as Parliament and Funkadelic (George Clinton even makes an appearance on the opening track). “King Kendrick” calls out any and every one on this track. It’s the one moment where Lamar most resembles the confident, braggadocios rapper that we saw in the aftermath of gkmc.

But this swagger and confidence eventually fade away. The album’s lowest point, “u” shows Lamar howling and shrieking “Loving you is complicated!” though the “you” could take on a double meaning of both Lamar himself or his fellow African-Americans, who interrupt the upbeat and positive “i,” the counterpart to this song.Whoever “you,” he eventually turns the mirror on himself when the beat switches to a moody, downright depressing saxophone in the background. In a voice that is almost on the verge of tears, he yells at himself in the mirror as he raps about his shortcomings and failures even after his status as one of Rap’s greatest. Failure to save his little sister from an unwanted pregnancy, failure to protect his little brother from violence in Compton, and failure to visit a friend dying in the hospital all haunt him. In a line that would floor anyone, he reveals that “if I told your secrets/The world’ll know money can’t stop a suicidal weakness.”

While Lamar never shied away from tackling heavy social issues, and this is his most politically charged work yet. With a new story of a young black man gunned down by a police officer dominating the media every few months, it’s no surprise that Lamar eventually snaps in anger. On “The Blacker the Berry,” he spits off some of the most aggressive and politically and racially charged lines we’ve heard from him. While the anger is real and genuine, he refuses to be completely fixated on it as he pulls out a twist ending. The entirety of the song is an angry, aggressive banger against white supremacy and institutional racism. However, Lamar calls himself (and by extension anyone else participating) a hypocrite for marching against white on black violence when he refuses to bat an eyelash against gang violence within his hometown of Compton (“So why did I weep when Travyon Martin lay in the street/When gangbanging make me kill a n*gga blacker than me/Hypocrite”).

The album ends with one of the most epic closers possible for a rap album. Lamar starts off “Mortal Man” rapping on his role within hip-hop as the voice for mature, conscious rap, hoping to further the message of Nelson Mandela whom he name checks several times throughout the song. The song eventually fades out to a mock interview between Lamar and Tupac. What’s frightening is how Tupac’s answers, taken from an interview in the mid 90’s, are still incredibly relevant even 20 years later. When asked what he thinks about the future of Lamar and his generation, Tupac answers with a pretty ominous warning: “I think that n*ggas is tired of grabbin’ shit out the stores and next time there’s gonna be bloodshed for real. I don’t think America know that … it ain’t gonna be no playing. It’s going to be murder.” A statement with even more weight behind it given the shooting of two NYPD officers by African American Ismaaiyl Brinsley this past December in response to murders of unarmed Eric Garner and Mike Brown.

To Pimp a Butterfly lacks the structured narrative of gkmc, but it is infinitely richer and more complex. Each song is a short vignette that provides insight into what it means to be black in a system (the music industry, and by extension, the American government) that continually attempts to strip them of wealth, identity, and culture. Lamar does not beat you over the head with philosophy and lectures. Like the unnamed narrator in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man which he alludes to with the yams line in “King Kunta,” Lamar strives to become an everyman. By providing you with his own experiences, successes, and failures, he hopes that you can connect in some way—big or small—to his own experience and learn from it. He is well aware that his 79 minutes of thought-provoking and emotional music will not spark a revolution nor will it end institutional racism. But that’s not really what this album is about. TPAB is about getting up every day in the face of an overwhelming, oppressive force and celebrating humanity in the face of it. It is clear that Lamar wants to affect the minds of his audience for the better.

This album is a testament to how phenomenal of an artist Kendrick Lamar is. He figured out how to work the defective mechanisms of the music industry to create something with both mass appeal and artistic merit on good kid, m.A.A.d city, and he could have easily repeated that formula on this album and enjoyed tremendous success and praise; but he didn’t. Instead, he rejected the system entirely. Nothing on this album is aimed at the radio or even at mainstream audiences. So much of the production harkens back to the music of the 60’s and 70’s, music that most of Lamar’s fans are completely unfamiliar with. Lamar himself stated that this album “wasn’t made for people in the suburbs.”

In an era where most rappers maybe drop a line or two about civil rights with the same passion and effectiveness as hashtag activism, Lamar dishes out responsibility and blame equally to black and white Americans, as well as himself, with the same energy and emotion that he has shown throughout his career. The fact that Lamar made an album at the pinnacle of his career that both rejects mainstream appeal (though the album still took the number one spot on the Billboards two weeks in a row) and refuses to shy away from being brutally honest and making listeners, especially white listeners, uncomfortable about the state of civil rights in America proves that Lamar is truly a once-in-a-generation artist along the likes of The Beatles, Michael Jackson, Kurt Cobain, and yes, Tupac. The result is an album that not only is an incredible piece of art, but one that fundamentally shifts the hip-hop genre. Only time will tell exactly what kind of change TPAB will have on hip-hop, but make no mistake about it; this is a damn near perfect album.

Oh, and it also just happens to sound fantastic as well.