By JARED THOMPSON – STAFF WRITER

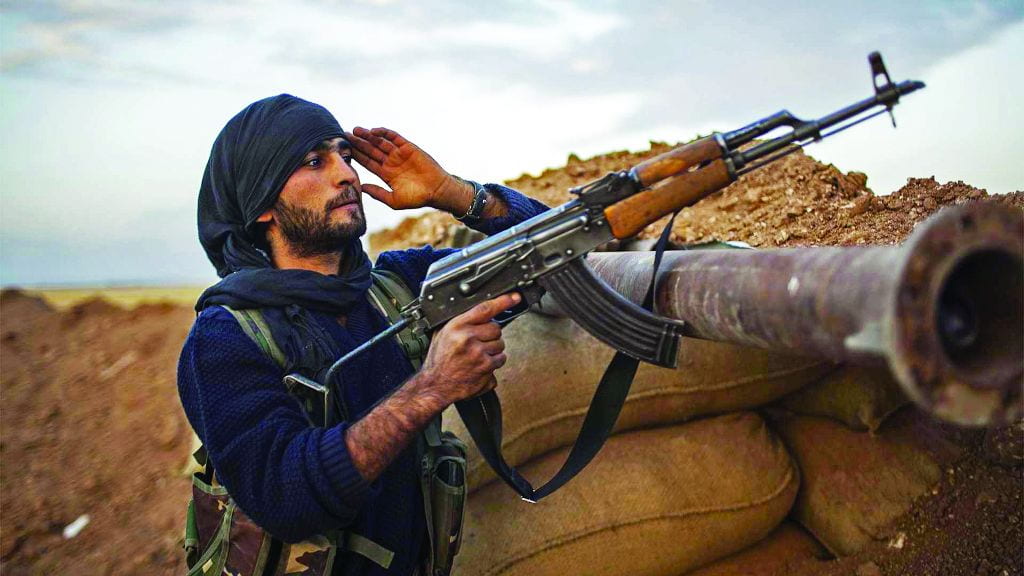

In recent weeks following the beheadings of two american journalists and one British aid worker , a jihadist group colloquially referred to as ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) burst itself onto the global scene.

This sudden emergence raises more questions about ISIS than answers, leading to chronic mischaracterizations and inflated exaggerations of ISIS and their global presence.

ISIS, or the Islamic State (IS) as they have recently rebranded themselves, traces its history to 1999 when it was founded as “The Organization of Monotheism and Jihad” by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a notable Salafi jihadist operating in Iraq during the coalition invasion and occupation of that country.

In 2004, al-Zarqawi aligned himself (and the group he founded) with the global Al-Qaeda network, upon which the group received the moniker of “Al-Qaeda in Iraq.” More recently, specifically in the wake of al-Zarqawi’s death in a coalition airstrike in 2006, the group adopted the name “Islamic State of Iraq” and took on a form similar to the one preoccupying the current news cycle.

In the time between 2006 and 2014, the group was driven back to its current center of power in northern Iraq and western Syria, but has more recently displayed an increased military capacity, capturing the Mosul Dam in northern Iraq and later occupying the city proper, looting United States military supplies and $429 million in Iraqi Currency from banks.

To properly understand IS, one must understand that IS brands itself as a caliphate with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as its caliph, thereby claiming religious authority over the global Islamic community.

However, as Assistant Professor of Religion Matthew Pierce points out, al-Baghdadi’s claim is a “slap in the face to most Muslims.”

“If people took [al-Baghdadi’s] claim seriously, they would flock to his caliphate,” Pierce said.

While currently fighting a war for geographic territory in Iraq and Syria, IS is also fighting to establish a social infrastructure based on an extremely rigid interpretation of Qur’anic Law that manifests itself in crucifixion being handed down as punishment for crimes, as VICE News captured in an August report.

IS’s interpretation of Qur’anic law aliented themselves from both non-Muslims and Muslims alike. Pierce pointed out that classical Islamic scholars vehemently disagree with this interpretation, and jailed cleric Abu Qatada recently denounced the beheadings of Foley and Sotloff from his Jordanian jail cell, where he awaits trial on terrorism chargers.

Denunciation from the global Islamic community, however, does not alter the fact that IS controls a considerable swath of territory in a region of the world currently characterized by chronic instability.

Assistant Professor of Politics and International Studies Dina Badie argues, “[IS] absolutely poses a threat to the populations of Syria and Iraq” and could potentially threaten a wider populace if IS were to gain control of a high-value target, such as oil production facilities or the Mosul Dam, which controls water flow to the population of Iraq living on the lower Tigris River.

This regional threat is only intensified by support from Sunni Muslims who are disillusioned with the Iraqi Government, which Badie argues that they have serious grievances with.

Forecasting in these situations is extremely problematic, whether it concerns the future of IS or the future of foreign attitudes and possible interventions. As both Badie and Pierce point out, reliable information (when it is available) is only current for a small time window, making policy extremely difficult to formulate and opinions challenging to solidify.

Regardless, Badie and Pierce would caution against the “bomb [IS] back to the stone age” rhetoric espoused by Texas Senator Ted Cruz at an Americans for Prosperity Summit in early September. Badie cautions that military solutions could be “counterproductive.”

Pierce heavily emphasizes the fact that this fight is an “intra-Muslim conflict” that the United States cannot lead the charge against because of the associated risk of inflaming sectarian violence.

This, however, doesn’t mean that IS is taken lightly by either professor. While Badie noted that ground troops could be inefficient, solutions could lie with unlikely bedfellows like the Assad Government in Syria or the Iranian Government, as the massive threat that IS poses in the region is far too great for either of the two powers to ignore.

To cast this as an abstract issue taking place in the Middle East, however, would do a disservice to those who it impacts on our own campus.

Sophomore Haidar Khan vehemently rebuked the legitimacy of IS, saying that he didn’t recognize the caliph, and called on the global Muslim community to “denounce this sort of behavior.”

Khan, who experienced anti-Muslim prejudices in the past, expressed concern that IS’s emergence gave people another opportunity to make misinformed generalizations about the Muslim faith as a whole.

The important piece to remember, according to Khan, was that “… the Islamic State is as Islamic and Stately as the Holy Roman Empire was Holy and Roman.”