By RACHEL KENT – CENTO WRITER

From the very first tour as a prospective student, each member of the Centre community is proudly told that Kentucky is the birthplace of Lincoln and that one time, the man himself borrowed some books from someone important who was connected to Centre.

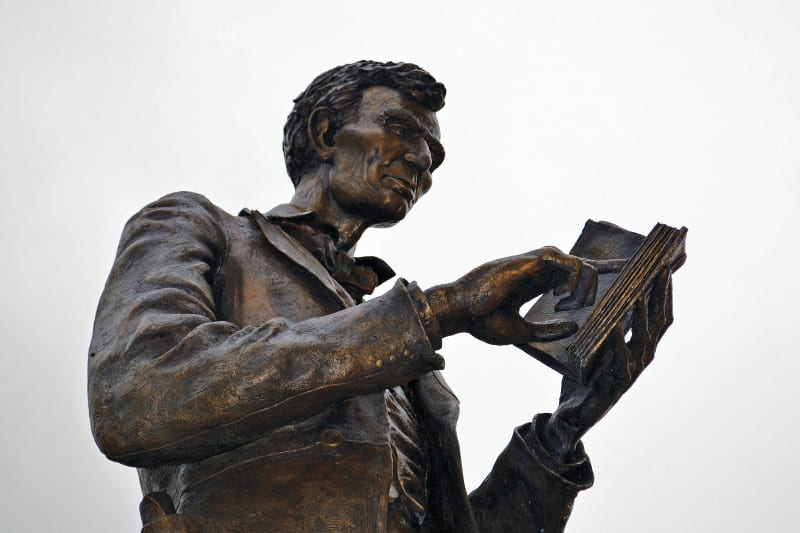

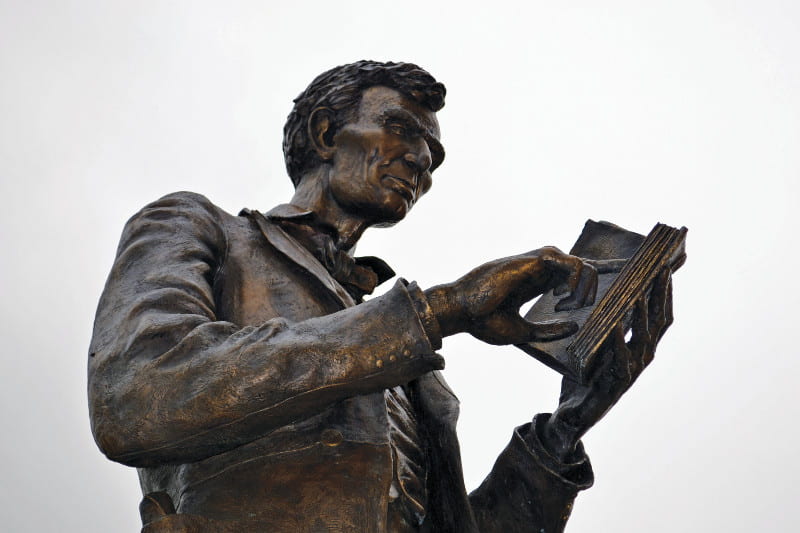

Somehow, because of this, we ended up with a gigantic Lincoln on our lawn–standing tall, collecting pennies, and providing good luck. The explanation rarely goes further, but looming a bronze statue of Abraham Lincoln continues to hold court outside of Crounse, silently watching over the academic quad.

One can’t help but wonder–why? What claim do we actually have to this man, one of the greatest presidents–and perhaps people–of all time? Why is he here? He did not attend our school, donate money, or contribute directly to the well-being of the college. Instead of erecting statues to anyone on the long list of distinguished Centre alumni, the statue is of someone who, while important, has relatively little connection to our school specifically.

To clear up the story that may or may not have been correctly relayed by that tour guide, John Todd Stuart, a personal friend of Abraham Lincoln’s and graduate of the Centre College Class of 1826, persuaded 23-year-old Lincoln to go to law school instead of becoming a blacksmith. Stuart provided Lincoln with the books he used to study for, and ultimately pass, the bar exam. The two went on to be law partners, and it can certainly be argued that without Stuart, Lincoln’s story (and indeed America’s) may have turned out very differently. Even if Stuart can lay proper claim to Lincoln, however, can Centre College?

Does it seem a bit like piggybacking? Does it even make sense? Throughout Kentucky, there are statues erected to political figures, religious personalities, sports celebrities, military heroes, even confederate leaders, all of whom have a tangible connection to their location. Yet our school takes pains to display our minor connection to an American president who might have needed Kentucky more than God but held no affection for Centre College. Is that even right for us to do?

The answer is about more than the fact that one Centre graduate had a pretty cool connection. Lincoln has come to be a figure to which everyone wants to lay some sort of claim. Illinois does its very best to point out that Lincoln lived in Springfield. Washington, D.C. made one of the most impressive monuments on the mall in his honor. As I toured other small colleges, he kept coming up–Lincoln stood here, Lincoln spoke about this, Lincoln read, Lincoln thought.

Clearly, Lincoln was a pretty important guy. There is no doubt about his contributions to the country as a whole, but if that’s what it takes to get a statue on Centre’s campus, should there not also be a gigantic bronze statue of John F. Kennedy? George Washington? Martin Luther King, Jr.? Does borrowing a few books from an old army buddy who happened to go to Centre make him any more “ours” than these other great people?

It may seem that it makes little sense to have picked him above some of the Centre grads who enacted change. Even Stuart himself may have more objectively “earned” a right to stand erect on our picturesque academic landscape. In my opinion, however, the “lay claim to Lincoln” fad, while perhaps overzealously popular, is a bandwagon we should not be ashamed to jump onto.

Over the years, Lincoln has become less of a man and more of a figurehead. Lincoln represents free thought, independence, justice, the struggle for morality in the face of difficulty, and, ultimately, what it means to be a good human being–all of which are at the core of what Centre holds dear. In this way, Lincoln transcends his tiny connection to Centre as a school and instead establishes a larger connection to Centre as an educational institution priding itself in instilling good values and creating functioning citizens.

Lincoln does not have to be just “ours”–Lincoln belongs to everyone, and that is what makes him great. As he stands there larger-than-life, students are reminded of his larger-than-life influence on the state, country, and world. He is not just a man who borrowed a couple of law books from John Todd Stuart. He is not just the most famous president, or the emancipator of the slaves. He is a symbol of what it means to do what is right instead of what is easy. He embodies the struggles of both the South of which we are a part and the country we call home.

Is then Lincoln more Centre’s than someone else’s? No. But I think there is absolutely nothing wrong with establishing a connection, however small, with someone so large – and someone who so perfectly embodies the kind of institution and history with which we identify.

So next time you’ve got a penny, pop over and have a moment with Lincoln. Make sure to let him know that someone from your school gave him some law books a long time ago, and he gave you even more in return.